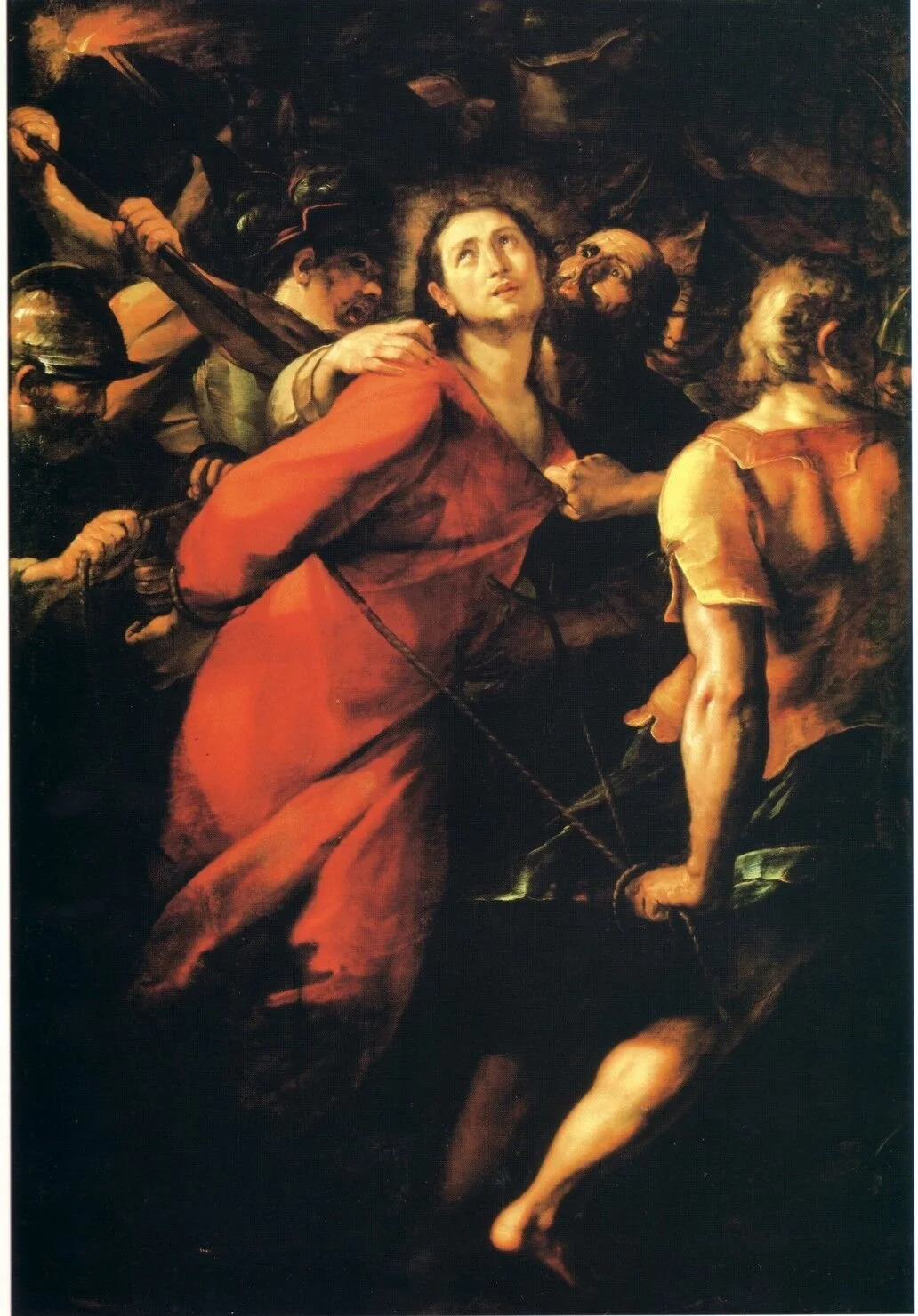

Giulio Cesare Procaccini

The Capture of Christ

Artist

Giulio Cesare Procaccini

( Bologna, 1574 – Milan, 1625 )

Details

Oil on canvas 210,8 x 142,2 cm Signed lower left: G.C.P.

Provenance

Possibly Abraham Darby sale, Christie’s, London, 8 June 1867, lot 99, as Giulio Cesare Procaccini Christ Led to Calvary, bought Cox; Tomás Harris, London, 1937 (photo in Witt Library, London); Private collection, Barcelona, by 1945 (see Literature); Piero Corsini & Maison d’Art, Monaco, by 1997, and with Agnew’s, London, (Millenium Exhibition, 2000, no. 6).

Exhibition

El Arte en la Passion de Nuestro Señor, exhibition, Barcelona 1945, no. 13; Genua Tempu Fà, exhibition in Monaco , Maison d’ Art, 1997; Procaccini in America, exhibition, New York, Hall & Knight Ltd, 2002. Le Meraviglie dell’Arte, Important Old Master Paintings, exhibition catalogue, Maison d’Art, Monte-Carlo, 2005.

Literature

M. Trens, El Arte en la Passion de Nuestro Señor, exh. cat., Barcelona 1945, no. 13; A. Pérez Sánchez, Pintura Italiana del Siglo XVII en España, Madrid 1965, p. 364; C.Thompson & H. Brigstocke, Shorter Catalogue. National Gallery of Scotland, Edinburgh 1970, pp. 70-71; N.Ward Neilson, “An altarpiece by Giulio Cesare Procaccini and some further remarks”, Arte Lombarda, no. 37, 1972, pp. 22-25 fig. 1; M. Valsecchi, in Il Seicento Lombardo, exh. cat. by G. Bora, M. Valsecchi, Milan, Palazzo Reale and Pinacoteca Ambrosiana, 1973, II p. 42, no. 78; H. Brigstocke, “Preview to the Lombard exhibition of 17th century art in Italy, an opportunity to study G. C. Procaccini’s chronology”, Connoisseur, 1973, p. 15; P. Cannon-Brookes, Lombard Paintings 1595-1630. The Age of Federico Borromeo, exh. cat., Birmingham, City Museum Art Gallery, 1974, p. 187; H. Brigstocke, ”Il Seicento Lombardo” (review), The Burlington Magazine, vol. C X V, no. 847, 1973, p.691; H. Brigstocke, Italian and Spanish Paintings in the National Gallery of Scotland, Edinburgh 1978, p. 108; idem, revised ed. 1993, p. 125 note ii; M. Rosci, Giulio Cesare Procaccini, Soncino 1993, pp. 42, 110; H. Brigstocke, in T. Zennaro ed., Genua Tempu Fà, exh. cat., Monaco, Maison d’ Art, 1997, pp. 7-13, no. 2; H. Brigstocke, in N. H. J. Hall, ed., Procaccini in America, exh. cat., Hall & Knight Ltd, New York 2002, pp. 90-93, no. 8, and under no. 9, pp. 94-97; Hugh Brigstocke, Le Meraviglie dell’Arte, Important Old Master Paintings, exhibition catalogue, Maison d’Art, Monte-Carlo, 2005, n.10, pp. 55 – 60, color ill p.57.

The Capture of Christ, with the kiss of Judas and the subsidiary scene of Peter and Malchus, was a traditional scene in the depiction of the Passion from at least the sixteenth century, when Dürer included it in all of his woodcut and engraved passion cycles. While in Italy Gaudenzio Ferrari incorporated it in his frescoed series of 21 Scenes from the Passion in S. Maria delle Grazie, Varallo, dated 1513. During the early seventeenth century by far the most important interpretation was Caravaggio’s painting for Ciriaco Mattei in Rome c. 1602 (now National Gallery of Ireland, Dublin): in this half-length design of horizontal format the Malchus episode was omitted and all attention is focused on Christ’s passive acceptance of his fate. The subject was then taken up by other artists in the circles of Caravaggio and Manfredi, including Manfredi himself (lost; known from an engraving in Teniers’ Theatrum Pictorium), and Baburen, who painted it three times, with and without Malchus (Borghese Gallery, Rome; Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; Longhi Collection, Florence). A little later Van Dyck painted three closely related versions (Minneapolis; Prado, Madrid; ex Corsham Court, now Bristol Museum and Art Gallery), all apparently dating from c. 1620 when he was still in Antwerp immediately prior to his visit to Genoa.

Procaccini’s painting, arguably his masterpiece which omits the Malchus episode, probably dates from 1616-20, when he was producing his most vibrant, vigorous and dramatic work, especially in Genoa. A baroque sense of lateral and diagonal movement, albeit within a relatively shallow space, is tempered by a mannerist concern with the expressive power of turning, twisted forms, clothed in angular faceted draperies. This picture is distinguished by its masterly deployment of nocturnal tenebrist light and a dramatic use of chiaroscuro inspired perhaps both by late Titian, in particular The Mocking of Christ, then in S. Maria delle Grazie, Milan, (now Paris, Musée du Louvre), and also by knowledge of works by Caravaggio that had found their way to Genoa . In this respect the Milanese artist appears to have approached his commission along the same lines as Van Dyck whose Corsham Court picture shows a similar dramatic concentration, focused like Procaccini’s on the heads of Christ, Judas, and one of the soldiers, and a comparable stylistic debt to late Titian and Caravaggio. Since there is broad consensus in dating Van Dyck’s picture before his visit to Genoa, where he and Procaccini might well have met, their respective pictures would appear to have been conceived independently.

Procaccini’s Capture of Christ is matched in his own oeuvre only by a small distinctive group of pictures of similar dimensions, showing further scenes from Christ’s Passion: The Flagellation in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; a Mocking of Christ in Sheffield; The Raising of the Cross in the National Gallery of Scotland, Edinburgh; a Deposition, unusually with Christ still nailed to the Cross, in London (Matthiesen Gallery); possibly a lost Pietà, published by Fernanda Wittgens ; and a signed Agony in the Garden, formerly in the collection made in the nineteenth century by the Vizcondes de Roda, Spain . It is not entirely impossible that all or some of these pictures originally formed part of a Passion cycle in some religious institution, in Italy or maybe Spain, where they escaped the attention of guide book writers. However no such cycle is documented, nor do any of the pictures under discussion have any early provenance to support such a hypothesis.

On the other hand a surprisingly large number of pictures by Procaccini related to The Passion turn up within a short space of time in English sales and exhibitions in the nineteenth century, a time when the Milanese artist was not a household name, which might suggest that they were imported together as a related group in the aftermath of the Napoleonic wars. Importations at this time from Genoa by the British art trade are surprisingly well documented and there are no references to such Procaccini paintings there which might instead suggest a Spanish source, or even a route via France. In 1830 a Crucifixion by G. C. Procaccini was recorded in the Literary Gazette as in the possession of Mr. Young of Craigs Court, and it is not inconceivable that this is an early reference to the Edinburgh picture. In 1836 a Deposition from the Cross was exhibited at Davidson’s Pall Mall Gallery in London and was also described in the Literary Gazette; and what appears to have been the same picture was then exhibited at Manchester Art Treasures Exhibition 1857 as from the Abraham Darby collection. George Scharf, who in the same year recorded its composition and its dimensions (84 1/2 x 58 in.), attributed it Camillo Procaccini (Sketchbook 45, National Portrait Gallery, London); but at the Darby sale, it reappeared under an attribution Giulio Cesare Procaccini and was paired with a picture of Christ led to Calvary (lot 99). The Christ led to Calvary cannot now be identified, unless it was in fact our picture of the Capture of Christ; there is a superficial similarity in these two subjects with Christ standing in a hostile crowd, and when Neilson published the present picture in 1972 it was described as The Way to Calvary. The Deposition can be firmly recognized from Scharf’s sketch as a Pietà which much later reappeared in a private collection, Milan, in 1933 when it was published by Wittgens. This might also be the Deposition by Procaccini which had been bought in at Nathaniel Strode sale at Camden Place. Meanwhile in 1853 a Mocking of Christ of Large Size by G.C. Procaccini is recorded with Charles O’Neill, a London picture dealer; this could well be the picture of this subject which has been in Sheffield since 1912. There is no specific reference during this period to a Capture of Christ; and the earliest firm provenance for the present picture dates from 1937 when it was with Tomás Harris, the London dealer.

Even without all this English documentation, Valsecchi, in 1970, had already proposed that the Edinburgh Raising of the Cross and the Sheffield Mocking of Christ might have formed a pair; and this stylistic comparison worked relatively well when the two pictures were exhibited side by side at Birmingham in 1974. Unfortunately at that date the Capture of Christ was known only from old photographs which precluded detailed stylistic comparisons. The same problem still applies to the Pietà (Wittgens, 1933); from the photograph it appears slightly more restricted in handling and might be from an earlier period, a view reinforced by the connected drawing in Stockholm which is similar in technique to the New York drawing for the Pietà of 1604 in S. Maria presso S. Celso, Milan. The Capture of Christ and the Boston Flagellation, juxtaposed for the first time in the New York exhibition of 2002, have appeared to be remarkably similar in style and are both signed with the artist’s initials in a similar format.